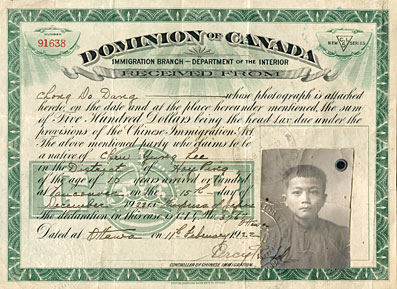

Primary Source Evidence

The Head Tax certificate of Chong Do Dang.

Library and Archives Canada, MG55/30-No166, reproduction copy number e008441646

The litter of history —letters, documents, records, diaries, drawings, newspaper accounts and other bits and pieces left behind by those who have passed on — are treasures to the historian. These are primary sources that can give up the secrets of life in the past. Historians learn to read these sources.

But reading a source for evidence demands a different approach than reading a source for information. The contrast may be seen in an extreme way in the difference between reading a phone book — for information — and examining a boot-print in the snow outside a murder scene —for evidence. When we look up a phone number, we don’t ask ourselves, “who wrote this phonebook?” or “what impact did it have on its readers?” We read it at face value. The boot print, on the other hand, is a trace of the past that does not allow a comparable reading. Once we establish what it is, we examine it to see if it offers clues about the person who was wearing the boot, when the print was made, which direction the person was headed, and what else was going on at that time.

A history textbook is generally used more like a phone book: it is a place to look up information. Primary sources must be read differently. To use them well, we set them in their historical contexts and make inferences from them to help us understand more about what was going on when they were created.